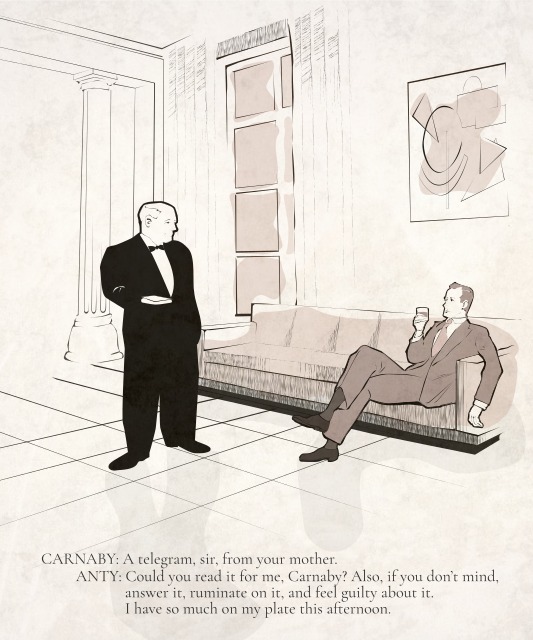

Example of spam, from this February’s newsletter and the seance scene in Foreboding Foretelling at Ficklehouse Felling.

Recently a global new methodology has been introduced to combat junk mail. The measure, in simple terms, requires that mass mailings be sent from a high-level domain the DNS settings for which include specific DMARC entries pointing to network-traceable reverse neuromix memblemeasures, the NOSTRIL values of which are furismically distributed. It’s a little more complicated than that, but that’s it in a nutshell.

And of course there was much rejoicing, because who likes spam? Your spam folder likes spam, that’s who, and in fact it likes it so much that, in conjunction with the above-mentioned counter-measures, it sometimes extends its reach beyond its grasp.

My very unscientific dart-in-the-dark analysis suggests that roughly half of Anty Boisjoly’s newsletters are being thusly diverted to the recipient’s junk mail folder. I’ve since implemented the required DNS changes (or, rather, I think I have — I may well have accidentally hacked into NASA) but, what with the notoriously closed-minded habit-prone practices of your poorly socialised email algorithm, once a spam always a spam.

So, if you signed up for the Anty Boisjoly intermittent newsletter and didn’t get one, there’s an excellent chance that it’s in your spam folder (or was once in your spam folder but has since been digested). If you add the source email address (pj.fitzsimmons@indefensiblepublishing.com) to your contacts or simply identify the newsletter as not spam, that should solve the problem for the future. If you can’t find it at all don’t hesitate for an instant to write and say so, again, to pj.fitzsimmons@indefensiblepublishing.com.

The latest number is out, by the way, and so if you don’t have the February edition announcing a new Anty Boisjoly, the next audiobook release date, a cryptic clue and two cartoons, and it’s not in your spam folder, it’s possible that you haven’t signed up yet. The solution for this, happily, is uncomplicated, and can be found here: https://indefensiblepublishing.com/newsletters/

The Case of the Case of Kilcladdich launched officially on March 1st, unofficially on February 21st, was on most platforms by February 23rd, and it’s available as of today, the ides of March, on Audible.

The Case of the Case of Kilcladdich launched officially on March 1st, unofficially on February 21st, was on most platforms by February 23rd, and it’s available as of today, the ides of March, on Audible.

Production is sufficiently advanced to lay claim to a publication date for the audiobook of The Case of the Case of Kilcladdich, Anty’s twisty misty whisky mystery.

Production is sufficiently advanced to lay claim to a publication date for the audiobook of The Case of the Case of Kilcladdich, Anty’s twisty misty whisky mystery. Somehow over the last year, on rare occasion, Anty Boisjoly escaped the books and appeared in several single-frame cartoons, inspired by the sort of thing that Punch was doing in the 1920s.

Somehow over the last year, on rare occasion, Anty Boisjoly escaped the books and appeared in several single-frame cartoons, inspired by the sort of thing that Punch was doing in the 1920s.

Two weeks ago was meant to be the official launch of Reckoning at the Riviera Royale audiobook and, technically, it was, except for Audible, who likes to play hard-to-get.

Two weeks ago was meant to be the official launch of Reckoning at the Riviera Royale audiobook and, technically, it was, except for Audible, who likes to play hard-to-get.